Artemisinin is a natural compound extracted from Artemisia annua, commonly known as Chinese sweet wormwood. First identified in the 1970s for its potent anti-malarial activity, it was licensed for clinical use in the 1990s and has since saved millions of lives from malaria worldwide. (Malaria is a mosquito-borne parasitic disease.) Its real-world impact earned its discoverers the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2015. Today, artemisinin is a widely studied plant compound in modern pharmacology, celebrated not only for its anti-malarial effects but also for its diverse applications in oncology, immunology, cardiology and neurobiology.

1. Multifaceted Anticancer Effects

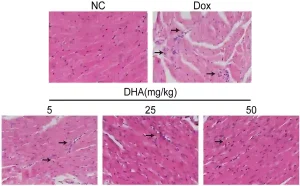

The same mechanism that underlies artemisinin’s anti-malarial activity may also explain its effects against cancer. In both parasites and cancer cells, artemisinin interacts with elevated iron levels inside the cells to generate reactive oxygen species, triggering oxidative damage and cell death. As both malaria parasites and cancer cells tend to accumulate more iron than healthy cells, artemisinin often leaves normal tissues unharmed. A favourable safety profile of artemisinin has also been confirmed in early-stage clinical trials involving patients with solid tumours. More research has uncovered that artemisinin also exerts oncosis, a form of cell death driven by cell swelling. By disrupting mitochondrial function and depleting cellular energy, artemisinin disables the ion pumps that regulate cellular balance. As a result, sodium and water rush into the cell, causing it to swell and eventually burst (Figure 1). This multi-pronged mode of action makes it harder for cancer cells to develop resistance against artemisinin.

Figure 1. Artemisinin causes cancer cells to swell and die through oncosis. The left panel shows a healthy, untreated cancer cell with a well-defined nucleus. In contrast, the middle panel shows an artemisinin-treated cell filled with large fluid-filled spaces and a swollen, pale nucleus. The right panel shows the cell is in a late stage of oncosis: the nucleus is bloated, and the cell membrane has started to rupture. Source: Du et al. (2010), Current Chemotherapy and Pharmacology.

2. Anti-Inflammation and Joint Health

Apart from its anticancer effects, artemisinin also exhibits potent anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in joint-related conditions. Two randomised clinical trials reported that artemisinin was efficacious at lowering inflammatory symptom scores in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Specifically, the participants reported better physical function and reduced joint stiffness, pain and swelling following artemisinin treatment compared to both baseline (before treatment) and the untreated group. Remarkably, some participants were even able to withdraw from their anti-inflammatory corticosteroid medications, a sign of meaningful clinical improvement. These clinical results align with prior pre-clinical research showing that artemisinin can suppress the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the joints and decrease the production of pro-inflammatory molecules in the lymph nodes draining the affected joints. These anti-inflammatory effects would then translate to healthier, less inflamed joints.

3. Cardioprotective Effects

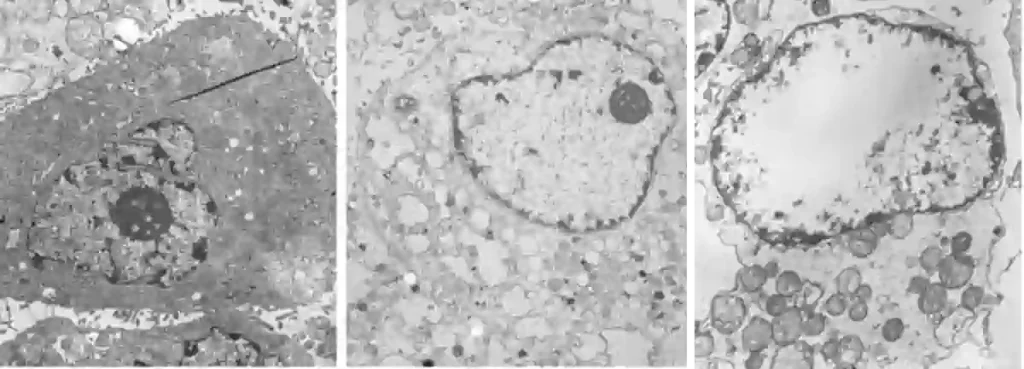

Recent pre-clinical studies have expanded the therapeutic scope of artemisinin to cardiovascular protection. In animal models of heart diseases, artemisinin has been found to dampen the severity of myocardial fibrosis (heart tissue scarring) and cardiac hypertrophy (heart wall thickening), which may contribute to heart failure if left unchecked. Interestingly, artemisinin could also mitigate the cardiotoxicity of certain chemotherapeutic drugs, supporting its use in complementary cancer care. Specifically, a 2024 study found that artemisinin rescued heart cells from damage caused by doxorubicin, a common chemotherapy drug (Figure 2). These cardioprotective effects appear to stem from artemisinin’s ability to calm overactive stress responses in heart tissues, particularly cell signalling pathways involved in fibrosis, inflammation and oxidative stress.

Figure 2. Dihydroartemisinin (DHA), the active metabolite of artemisinin, protects heart tissues from damage caused by chemotherapy. In the untreated cells (NC), heart muscle fibres appear smooth and orderly. In contrast, the doxorubicin-treated cells (Dox) are visibly damaged and disorganised, with signs of cell clumping and breakdown (black arrows). Treatment with increasing doses of DHA (5, 25, and 50 mg/kg) progressively reduced these signs of damage, restoring tissue structure. Source: Lin et al. (2024), The FASEB Journal

4. Neuroprotective Effects

The neuroprotective capacity of artemisinin is also gaining scientific recognition, especially when artemisinin could cross the blood-brain barrier. Studies have found that artemisinin alleviated neuronal and microvessel damage in the brain in animal models of dementia and stroke, leading to notable improvements in cognitive function. In these studies, artemisinin also curbed neuroinflammation and promoted the survival of neural stem cells in the brain, allowing neurons to regenerate to some extent after injury. Moreover, artemisinin activated the brain’s natural antioxidant systems to suppress oxidative stress, allowing healing and neural regeneration to take place. Collectively, these findings highlight that artemisinin could exert its therapeutic effects on multiple organ systems, underscoring its promising use in holistic and general health.